In the United States, the language of “racial reconciliation” is increasingly invoked in churches, corporate boardrooms, nonprofit organizations, and political platforms. Yet too often, the process is led and defined by the descendants of those who benefited most from racial injustice, rather than those who bore its deepest wounds. This imbalance not only distorts the process but also undermines its potential to be genuinely transformative.

True racial reconciliation cannot be orchestrated by those who have historically held the power, dictated the narratives, or controlled the systems of wealth and influence. It must be led by those most impacted by racial violence, dispossession, and systemic exclusion. Anything less risks becoming either a symbolic gesture or, worse, a retraumatizing reenactment of colonial power dynamics dressed in the language of healing.

When descendants of slaveholders, colonizers, or beneficiaries of racial hierarchies lead the reconciliation process, the outcomes often center on comfort and image management rather than truth, justice, or repair. Apologies are issued, but no reparations follow. Dialogues are held, but decision-making remains centralized in historically white institutions. Workshops are facilitated, but budgets remain unequally distributed. These patterns reinforce the status quo, pacifying discomfort without redistributing power.

This dynamic also privileges the emotional ease of the dominant group. The goal becomes creating a sense of closure, of “moving on,” rather than honestly confronting the enduring consequences of racial harm, including generational poverty, institutional mistrust, educational disparities, cultural erasure, and political disenfranchisement. In this sense, mainstream racial reconciliation efforts often cater to white guilt and fragility rather than Black trauma and resilience.

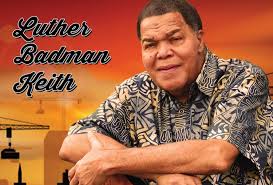

Having lived in the Black Christian evangelical world for the past 35-plus years, I have witnessed firsthand, across a wide range of Christian organizations, the bastardization of the concept of racial reconciliation. Sadly, even many Black Christians have internalized these diluted versions. As a result, the underserved — especially Black believers — have been marginalized within evangelical spaces, excluded from preaching opportunities, board leadership, and publishing platforms. Even when access is granted, it often benefits the individual rather than the broader community.

One of the critical missing links in all of this is the power of the Holy Spirit. As John 3:30 reminds us, “He must increase, and I must decrease.” The Spirit empowers us to think differently — to imagine reconciliation not as a symbolic gesture, but as a transformative, systemic process rooted in humility and divine justice.

There’s an expression that says, “Power concedes nothing.” Jesus understood that. In fact, He changed the game. He led with a radically inclusive vision — one that built a level playing field for all people, especially the poor and the oppressed. His Beatitudes are a blueprint for this reversal of worldly power: “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth” (Matthew 5:5).

If biblical reconciliation is to reflect the heart of Christ, then power must be conceded, and systems must be redesigned and transformed. Acknowledgment and apology alone are not enough. What is needed is a rebalancing of power, voice, and resources. This shift must be systemic, not symbolic.

Here are five key principles I believe are essential for genuine reconciliation:

1. Leadership by the Wounded

Those most harmed — descendants of enslaved people, Indigenous communities, and historically marginalized groups — must lead the process. Their lived experience must shape the design, language, timeline, and goals of any reconciliation efforts. Healing must be led by those who know the pain.

2. Narrative Control

The stories and frameworks used to guide reconciliation must come from the grassroots. This includes centering oral histories, truth commissions rooted in community, and cultural practices that reflect the values of the oppressed, not sanitized retellings curated for institutional comfort.

3. Structural Reparations

There can be no true reconciliation without a material response. That means wealth redistribution, divestment from oppressive systems (such as the prison-industrial complex and exploitative corporations), and reinvestment in Black, Brown, and Indigenous futures.

4. Shared Governance

Institutional power must be shared — or surrendered. Boards, churches, universities, and civic bodies must include and empower those who were previously excluded, not as tokens but as equal—if not primary—stakeholders in decision-making.

5. The Right to Say “No”

True reconciliation honors the right of harmed communities to decline participation in performative or insufficient efforts. They must be able to reject gestures that do not lead to meaningful change and protect their own boundaries around trauma and healing. Without consent, any effort risks becoming a reenactment of control.

The future of racial reconciliation in America depends on a righteous disruption of the old frameworks. We must unlearn models that prize politeness over justice and comfort over truth. We must reject the temptation to “move on” before we’ve even faced the truth.

Churches, Christian organizations, universities, and governments must go beyond panels, pledges, and performative diversity campaigns. They must make room for radical honesty, historical reckoning, and the tangible restructuring of power. Without this, what is meant to heal will only deepen the wound.

This is not about revenge — it is about repair.

It is not about guilt — it is about justice.

It is not about erasing anyone’s humanity — it is about finally affirming the full humanity of those whose dignity has been denied for generations.

The path toward racial healing must be built by those who know the terrain of suffering and survival best. Their leadership is not only legitimate but also essential. Until we understand that reconciliation without justice is not true reconciliation, we will continue to mistake performance for progress.

Now is the time to shift the center —

From the privileged to the oppressed.

From symbolic gestures to systemic change.

From control to shared liberation.

Only then can the body of Christ begin the work of true reconciliation — not as a moment, but as a movement. I’m just saying…. What say you?